An update from the soybean and pulse agronomy research program

Kristen P. MacMillan, MSc, PAg, Agronomist-in-Residence, Department of Plant Science, University of Manitoba – Spring 2021 Pulse Beat

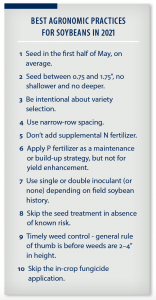

Soybean agronomy research has come a long way in Manitoba over the past decade — more than a dozen agronomy topics have been studied and nowcontribute to best management practices. Over the past four years, I’ve studied soybean seeding dates, variety choice, seed depth, fungicide use and iron deficiency chlorosis. Other Manitoba researchers have studied supplemental N fertilizer, P and K fertilization, weed control, preceding crop, row spacing and seeding rates. Inoculants and seed treatments have been explored in the MPSG On-Farm Network.

Amidst the findings, there are few “silver bullets” to increasing soybean yield — that is, single practices that consistently deliver double-digit yield increases (unless you forget inoculant in a new soybean field or spray weeds that are taller than your boots). But each practice has led to small, incremental findings that together result in greater profitability. A good way to describe the value of good agronomic practices is by applying the 5% rule — a well-known concept that has been popularized in farm management.

“A 5% increase in yield, a 5% decrease in costs and a 5% increase in price received will produce more than a 15% increase in net returns. The effect is cumulative, multiplicative and compounding.”

—Danny Klinefelter, retired farm economics professor, Texas A&M University

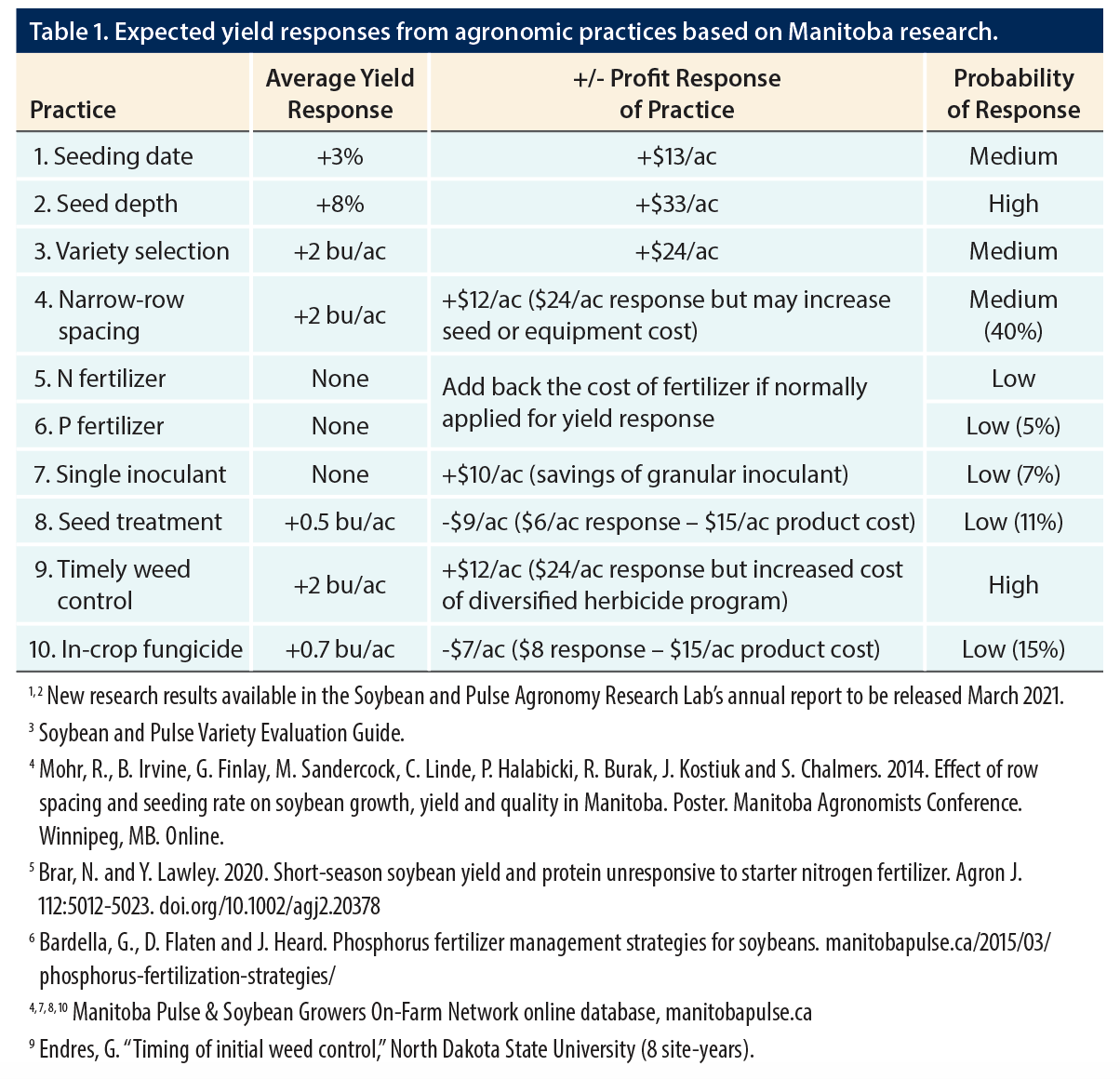

These days, we’ve far surpassed the 5% increase in price received. And since this is about agronomic practices, we’ll focus on yield responses and cost savings. Table 1 summarizes agronomic yield response outcomes for soybeans that have been well studied in Manitoba over the past decade. This provides the opportunity to assess your soybean agronomy practices and identify areas that could be improved. Chances are, you are already implementing some of these practices, so I’ve identified a couple of scenarios where just two practices are changed. Hopefully, it convinces you that even small changes add up.

Assumptions for the table and scenarios include a five-year average soybean yield of 34 bu/ac, a new crop soybean price of $12/bu and total operating and fixed costs of $375/ac. Further reading on each agronomic response is available in the footnotes. I’ll pose the last disclaimer as a question — will these practices and yield responses look the same for every field, every year? No. They may not even look the same for entire fields as precision agriculture research takes a foothold. Successfully applying agronomic data into practice requires an understanding of context — field history and characteristics, environmental conditions, regular scouting, commodity and input prices, evolving research findings and their interactions.

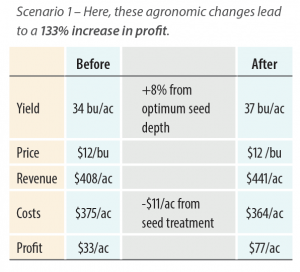

Scenario 1 – Adjust seed depth and skip the seed treatment.

Instead of being tempted to seed soybeans deep into moisture or shallow for quick emergence under good soil moisture, make sure that soybeans are seeded between 0.75 and 1.75″, as close to 1.25″ as possible. New Manitoba research has shown the detrimental effect of seed depths outside this range. Unless there are certain pest risks in a field, the probability of yield response to soybean seed treatment is only 11% based on 44 on-farm trials.

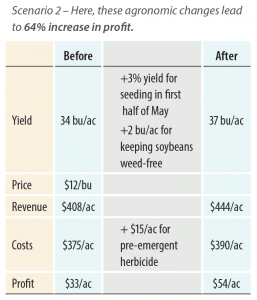

Scenario 2 – Seeding earlier and managing weeds on time

Instead of waiting for May long weekend or for all the canola to be in, consider seeding soybeans earlier if soil and weather conditions are favourable. This is especially true among farmers who have been dealing with spring canola challenges like flea beetles. Once the crop is seeded, scout regularly and ensure weeds are managed before they are 2–4″ in height. Soybeans are poor

competitors with weeds and dirty soybean fields equates to yield loss.

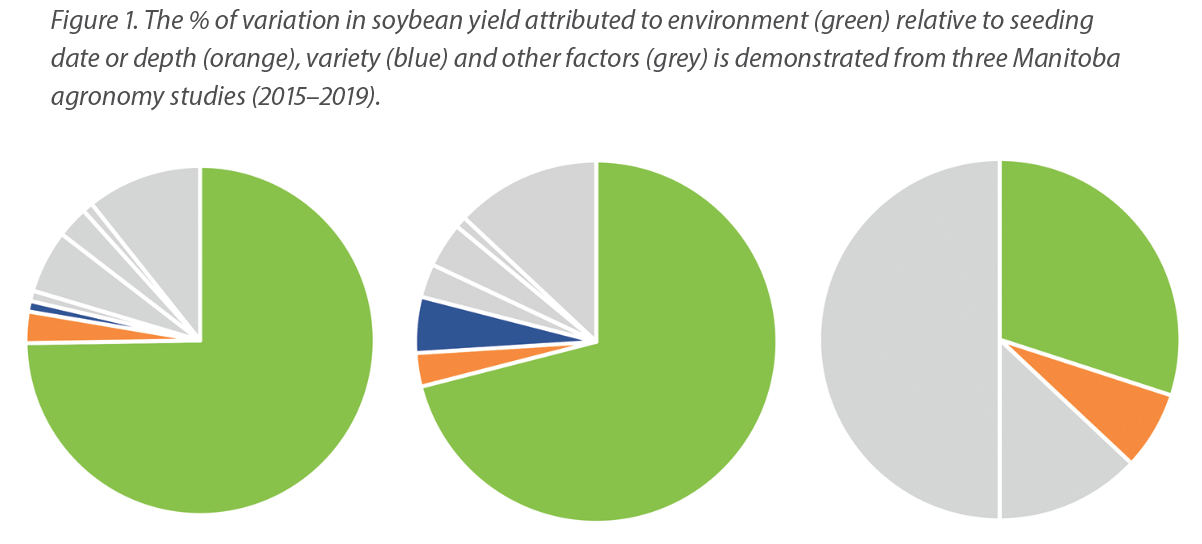

Agronomy and environment go hand in hand

Environment has accounted for the majority of soybean yield variation in several of these agronomy studies (Figure 1). For example, in my most recent soybean seeding date study, soybean yield ranged from 20 to 65 bu/ac across 12 environments, yet from only 33 to 39 bu/ac across four seeding dates. Certain weather and soil conditions are more favourable for soybean production, regardless of best management practices. The 5% rule can also be applied to land management, i.e., adopting practices that build soil organic matter and water holding capacity will likely lead to greater yield potential. Ongoing studies continue to relate water availability to soybean yield potential. One example might be adopting rotational tillage, where tillage is reduced or eliminated in one phase of your crop rotation. This doesn’t minimize the importance of agronomy but rather emphasizes that a focus on both agronomy and environment is warranted. After all, my favourite definition of agronomy states it quite simply…

“Agronomy is the study of soils and plants, [application to] the practice of field crop production and the management of land and water resources.”

— University of Manitoba